Bengaluru is often in the news for water scarcity related reasons. Doomsday warnings, talks of “Day Zero” hog the headlines.

In the recent past, the summer of 2024 stands out for these reasons as water scarcity hit most parts of the city after the rains failed in 2023. With the Cauvery reservoirs not getting filled from the monsoons, the city was staring down a pretty empty barrel. The brunt of the demand from the thirsty city was borne by ground water.

The Dynamic Ground Water Resources of Karnataka, is an annual report from the Groundwater Directorate and Groundwater Authority, Government of Karnataka. It has detailed information at district and Taluk level on ground water extraction and replenishment.

In this analysis, we look at the report from 2024 to understand how the failed monsoons affected ground water usage across the state, as well as specific parts of Bengaluru.

Calculation of groundwater extraction

At a crude/heuristic level, ground water numbers are computed using factors like rainfall received, the area over which it rained, and natural discharges into rivers and the sea.

The annual amount of rainfall over an area defines the amount of groundwater recharge. Higher rainfall means more ground water recharge, and a larger district/Taluk has higher volume to recharge compared to a smaller district/Taluk which receives a similar amount of rainfall.

Once you have this total recharge, there is natural discharges where water flows away to rivers, the sea etc. The computation in the report assumes that 10% of the annual ground water recharge flows away in this manner, and the rest 90% flows into the ground water table. This final 90% is the “annual extractable amount”.

For instance, if a district received 1 million litres of water as rainfall over its area, 0.1 million litres is assumed to have flown away to the sea and rivers, and 0.9 million litres is assumed to have ended up in the ground water table and is its “annual extractable amount”.

Now, if the district uses more than this 0.9 million litres, it is “over-exploiting” ground water, but if it uses less than 70% or 0.63 million litres, it is considered safe. The categories of usage are defined as below.

| Stage of Groundwater Extraction | Percentage of water extracted |

| Safe | 0 – 70% |

| Semi-Critical | 70 – 90% |

| Critical | 90 -100% |

| Overexploited | Over 100% |

How can an area extract more water than was recharged? This means that the excess water over the annual recharge came from what is called “Fossil Water”, which is the water that was already there in the groundwater table over the past years when the extraction might not have been as much as now.

Think of it is as living beyond your income, where the extra money comes from your savings and investments. Over time, you end up depleting your savings and investments and eventually you end up bankrupt. In ground water terms, it is called “Day Zero”.

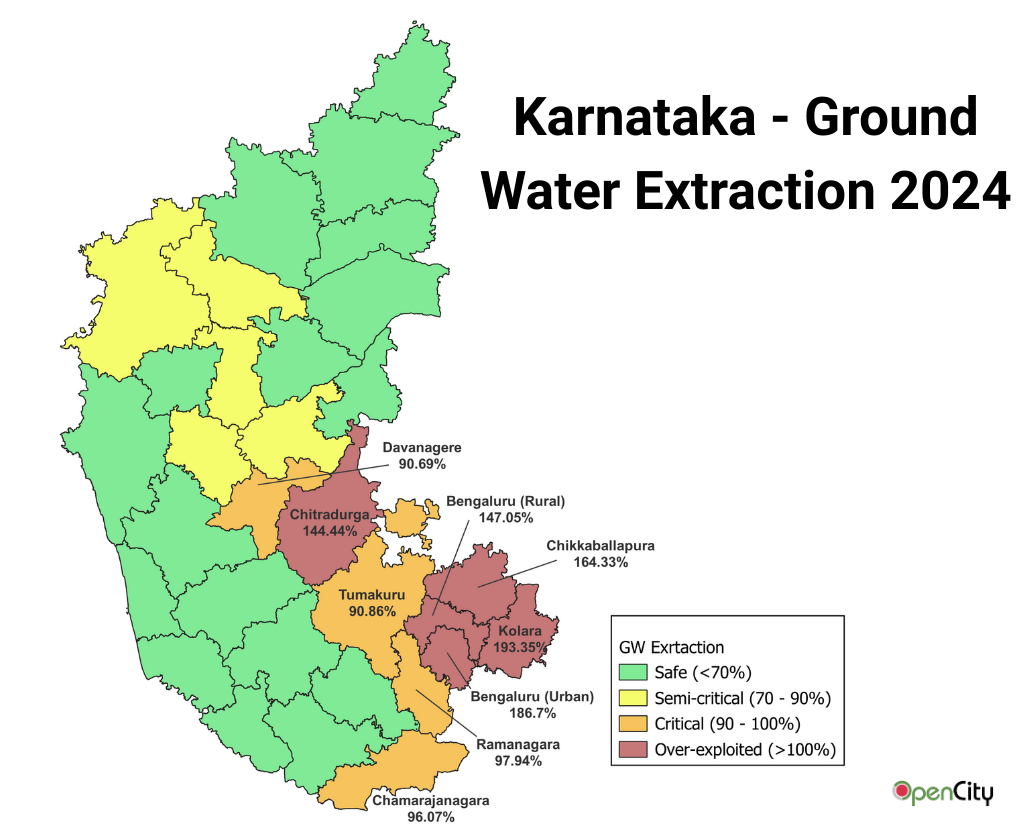

Ground water usage in Karnataka

Ground water extraction in 2024 was highest in the south-eastern parts of Karnataka, in the districts surrounding Bengaluru Urban. Along with Bengaluru, Kolar, Chikkaballapura, Bengaluru Rural and Chitradurga extracted well above what was recharged.

Tumakuru, Ramanagara, Chamarajanagara and Davanegere extracted almost every drop of water that was recharged.

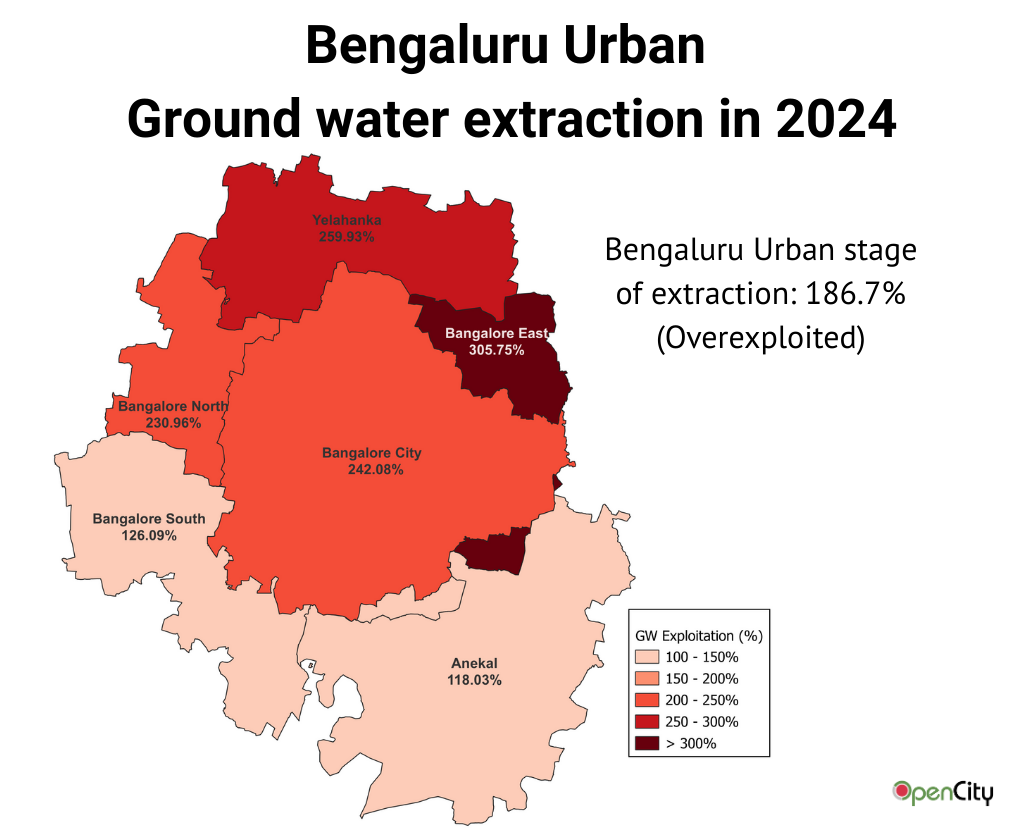

Ground water usage in Bengaluru Urban district

Within Bengaluru Urban district, while all Taluks were over extracting, some had much higher extraction than others. Bangalore East Taluk used up more than thrice the amount that got recharged, while North, Yelahanka and the City (GBA area) used more than twice of what was recharged.

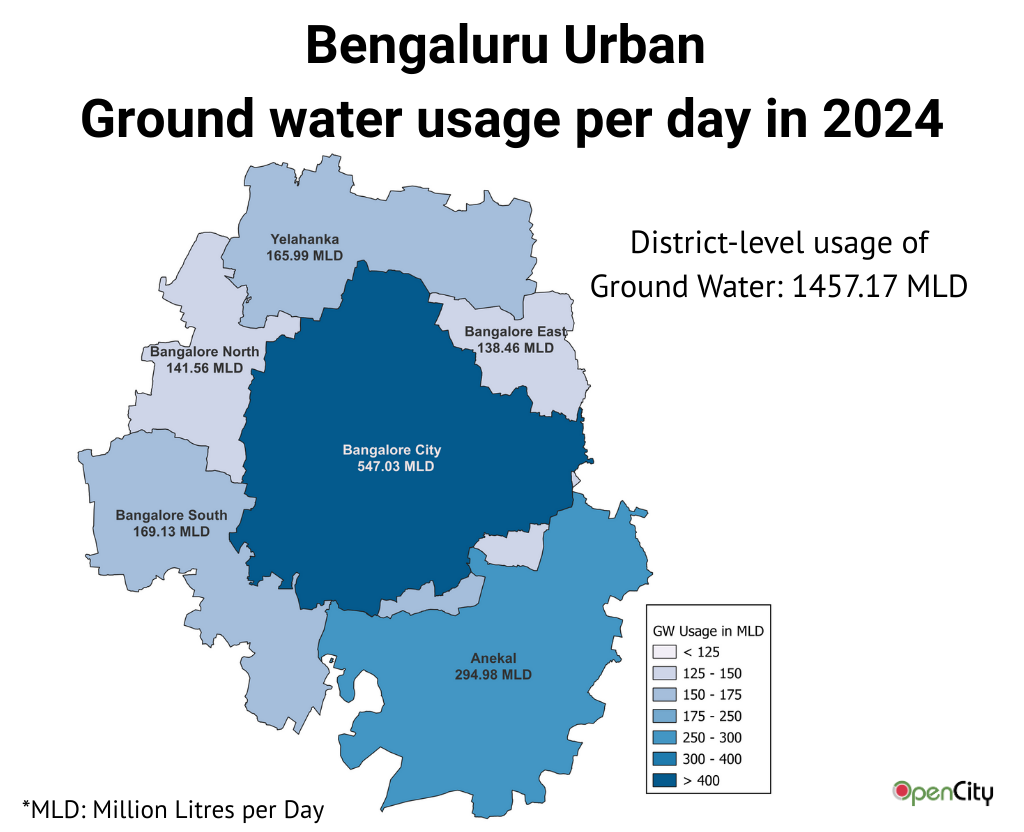

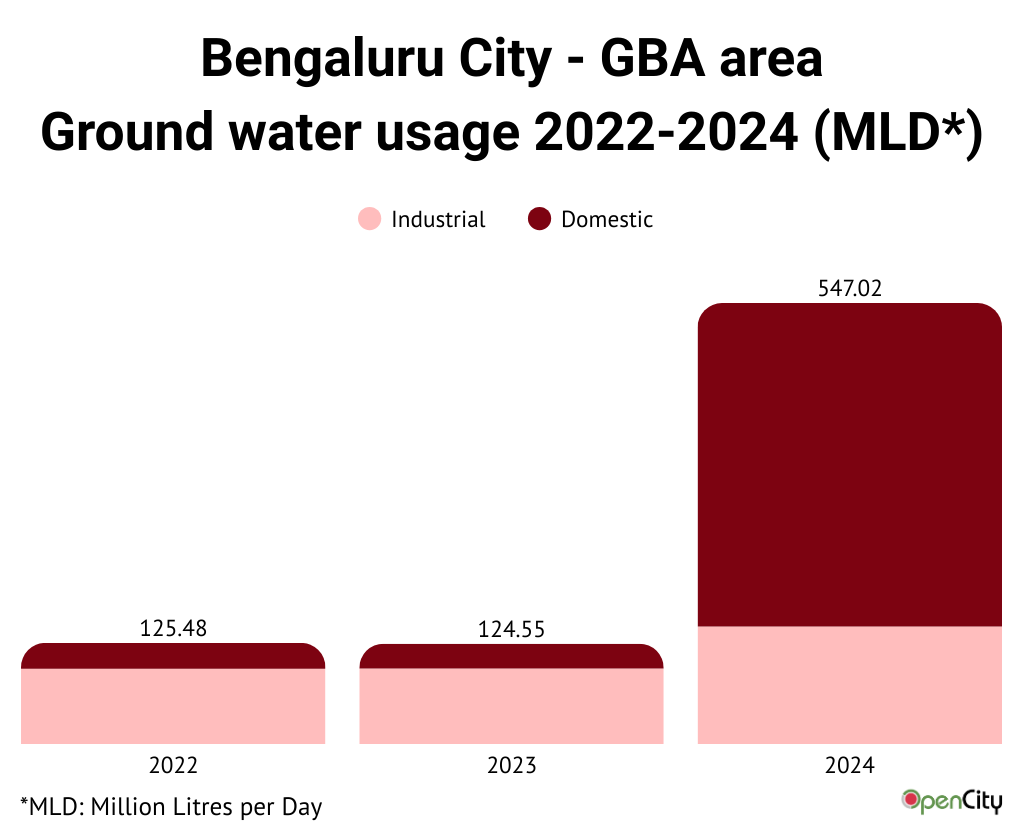

What does this usage mean in real terms, as litres consumed? The Corporation area, consumed 547 Million litres per day (MLD) , followed by Anekal at close to 300 MLD.

How can Bangalore East have an extraction of 305% but use up only 138.46 MLD? Extraction percentage is a factor of rainfall as well as area. This means that for the area under consideration 138.46 MLD was a very high usage, while sustainable usage would be under 45 MLD, where for Anekal, while the extraction was only 118%, the actual amount of water was 295 MLD, meaning, that the sustainable usage was around 250 MLD given the much larger size of the area.

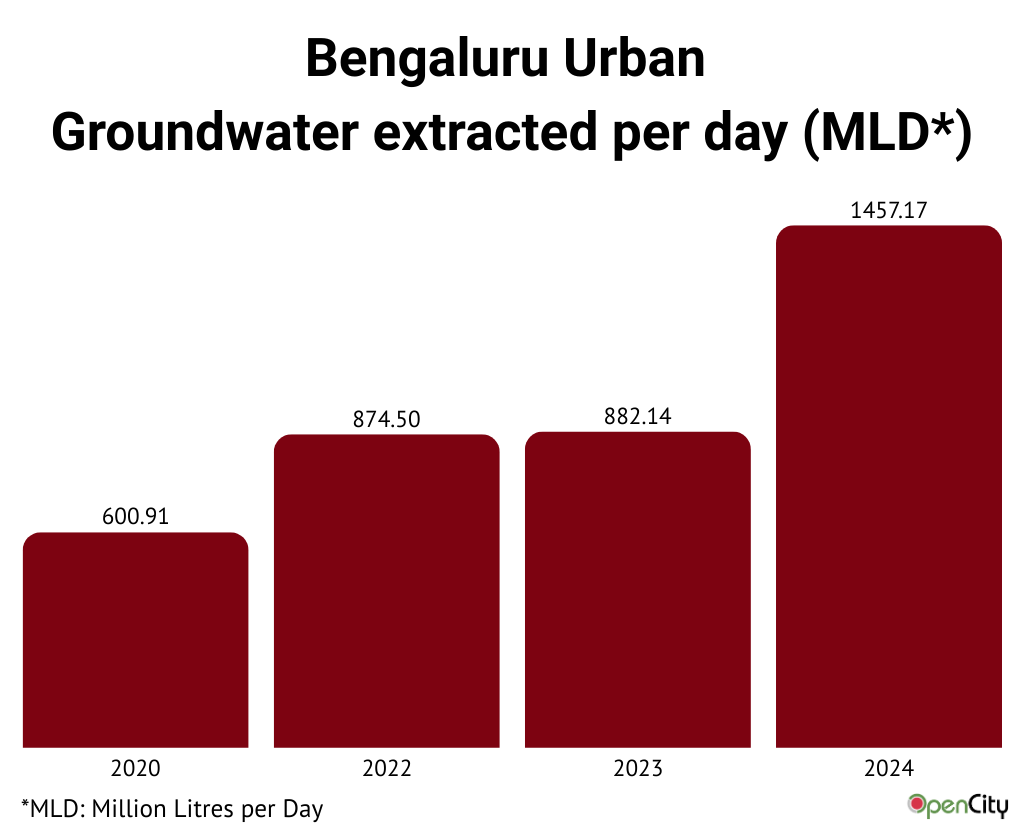

The groundwater extraction of Bengaluru Urban district has only been increasing, doubling from 600 MLD in 2020 to a very high 1457 MLD in 2024. While 2024’s usage could have been because of the drought in 2023, it needs to be seen if the number comes down during the next couple of years.

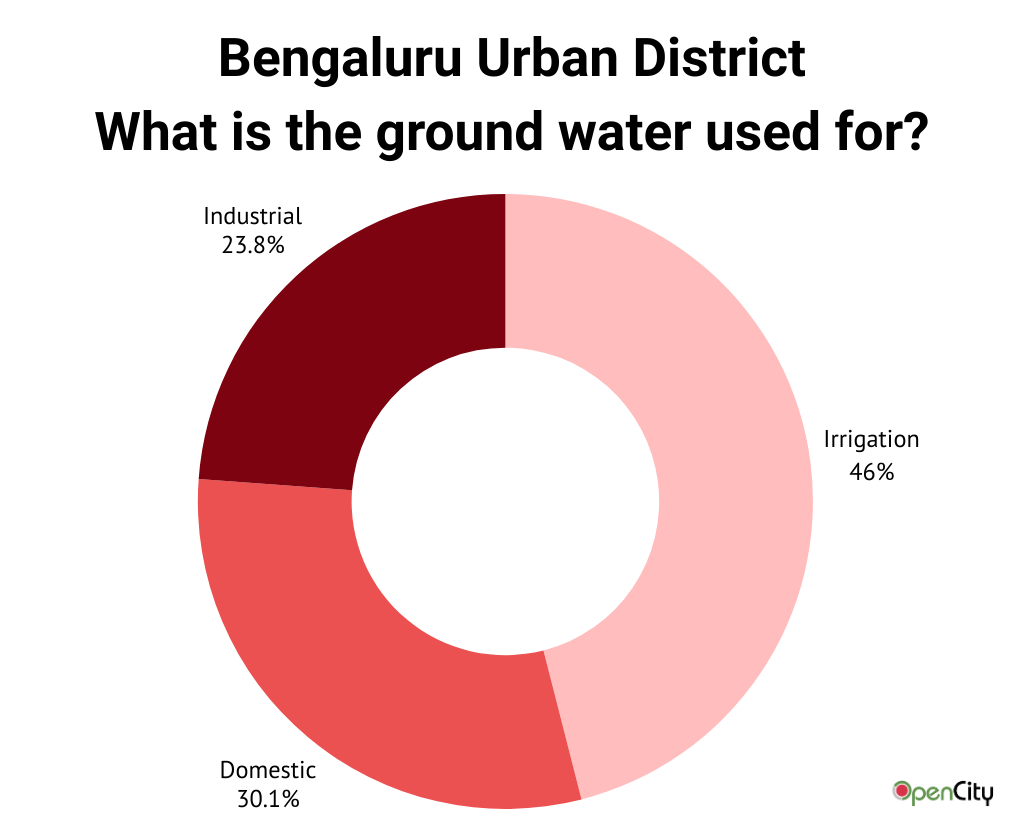

Large parts of Bengaluru Urban district, outside the corporation limits, fall under agricultural use, which is mainly fed with ground water. Close to half the ground water extracted was used for irrigation, while 30% was consumed for domestic purposes, with the rest used for industrial purposes.

However, given the high dependence on water tankers in Bengaluru for both domestic and industrial use, water extracted in agricultural areas could be used in other areas for other purposes. It is not clear if the report accounts for such variance in usage.

Ground water consumption in Bengaluru City

Since 2022, the report has been considering the BBMP area as a separate Taluk with details for other Taluks subtracted for the corporation area. This means that Bangalore North, South and East taluk values represent the areas of these Taluks outside of the corporation area from 2022 onwards.

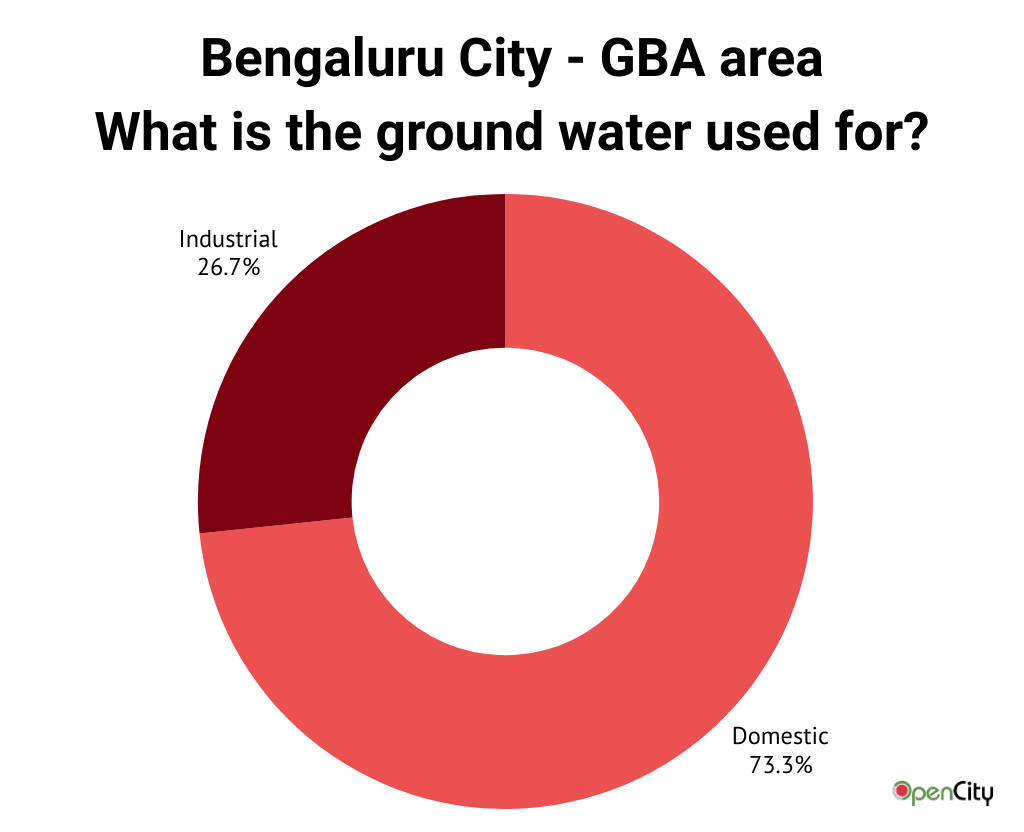

Within the city corporation limits, the usage of ground water is split between domestic and industrial with no irrigation use recorded. Not surprisingly domestic usage accounted for 73% of the ground water extraction with the rest used by industries.

However, the ground water usage in the city area more than quadrupled during 2024, likely because of the drought in 2023. Interestingly, the surge has been driven heavily by domestic usage which used to be much lower than industrial use in 2022 and 2023. Whether the numbers will normalise in 2025 and 2026, as the rainfall in 2024 and 2025 was good, needs to be seen.

Ground water is a precious resource, which can not only be used sustainably, but also replenished proactively. The report considers that 90% of the rainfall received goes towards recharging underground aquifers. In most areas, especially in our cities, this number would be a huge exaggeration given the high concretisation.

This means that the amount of water we are extracting is likely much higher than claimed by the report, and we are much closer to Day Zero than what the calculations imply. Solutions like extensive rainwater harvesting across the city to better recharge underground aquifers, using of treated wastewater for industrial use, construction and for semi-domestic purposes like watering plants to reduce the dependence on ground water are the need of the hour in ground-water dependent cities like Bengaluru.