Chennai is a city surrounded by large lakes which are important sources of water for the parched city. Many smaller lakes have vanished over the course of time, sacrificed at the altar of the relentless urban development juggernaut. Area names with prefixes like ‘eri’, ‘thangal’ etc suggest erstwhile lakes and tanks that have been built over.

Chennai’s lakes function not only as important water supply reservoirs but also as groundwater recharge points and help with flood mitigation during heavy rainfall events. Despite their important functions they are vastly neglected, and suffer from pollution through sewage and industrial effluents, and encroachment from surrounding properties.

Chennai lakes datajam

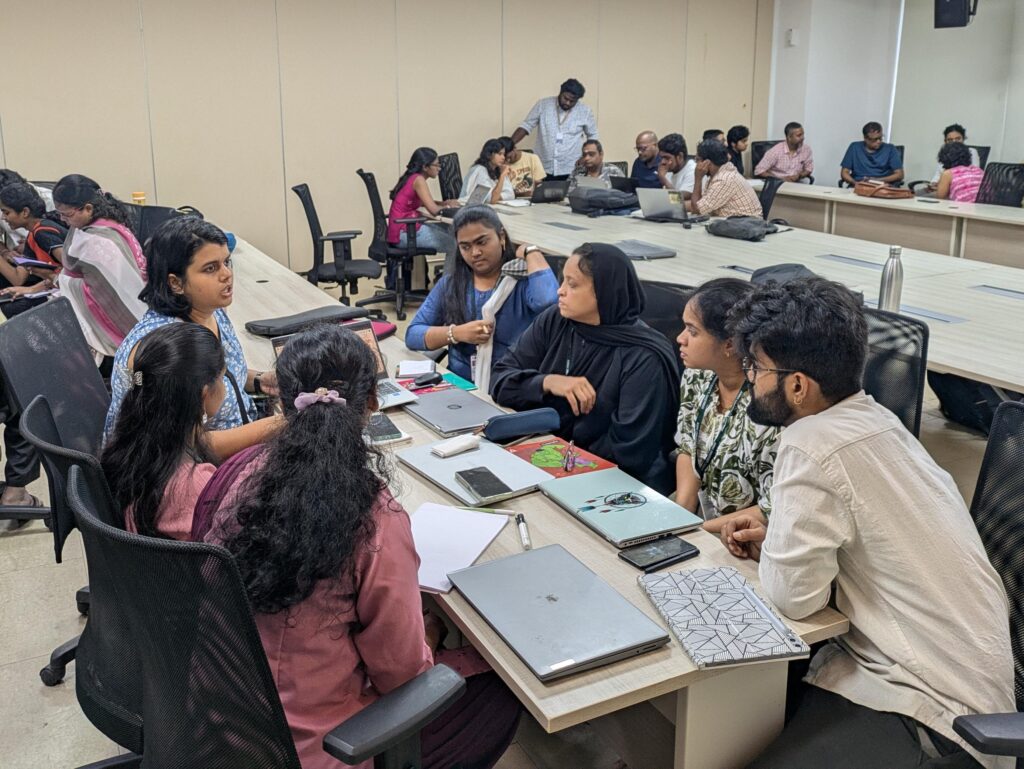

The Chennai Lakes Datajam was conducted by OpenCity in this context on the 27th September, 2025 at IIT-M Research Park, Tharamani, Chennai. The event was organised in partnership with WELL Labs, CAG Chennai, Poovulagin Nanbargal, Care Earth Trust and Reach the Unreached.

In the day long event, 34 participants from diverse backgrounds – GIS experts, students, researchers, civic activists, urban planners, architects and active citizens – split among five teams, looked at data to understand the lake systems in Chennai.

The teams used data from satellites, historic information in the public domain and their lived experiences around specific lakes to answer questions about the lake systems. Each team looked at a different lake system identified by the common river or canal that connected them.

Problem statements

Each team picked a different lake system based on the river or canal that connects them. The rivers and the lake systems they picked were:

- Kosasthaliyar river system with the Puzhal lake as the main lake.

- Kodungaiyur Canal system which is a part of the Kosasthaliyar system, but made up of the lakes – Ambattur, Korattur and Retteri lakes among others.

- The Adyar river system with the Porur and Ramapuram lakes

- The Koovam(Cooum) river system with the Chetpet lake and other lakes

- The Southern Kovalam lake system with the Perungudi, Velachery and Perumbakkam lakes along with the large Pallikaranai marshland as part of the system.

Outputs

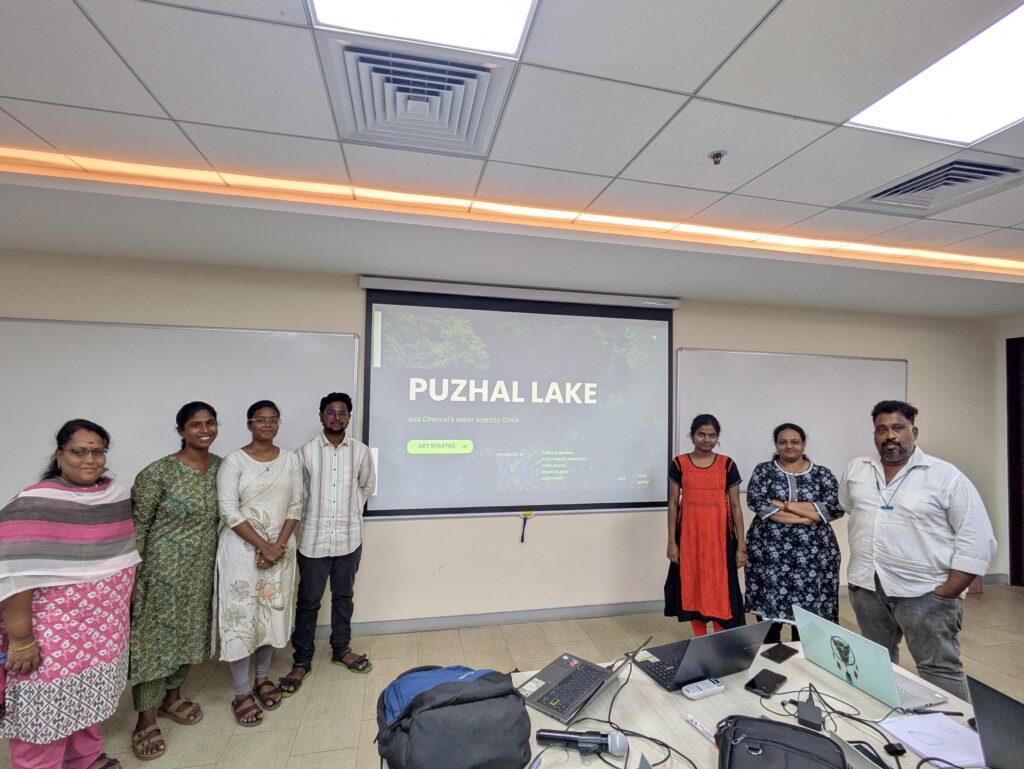

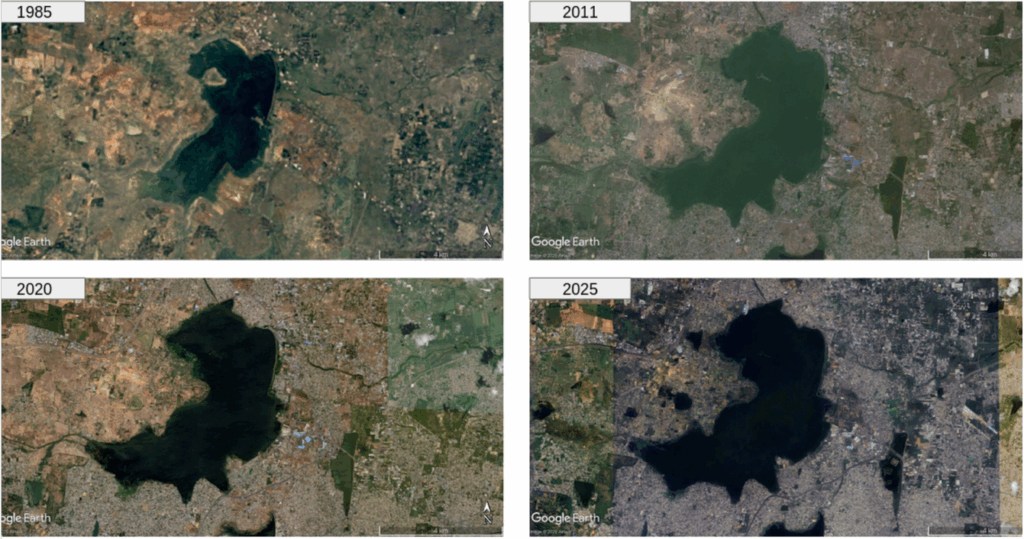

Kosasthaliyar River System

Alagu Maha Smiruthy, Anbu Arasu, Carol Shekinah, Gowthami, Mano and Shubhakarini looked at the Puzhal lake and how it is tied intricately to Chennai’s water supply system. They noted that the lake is fed from two directions, the Krishna river through the Poondi reservoir and the Kosasthaliyar river through the Cholavaram lake.

While the lake was historically used only for irrigation, in recent times it has served only the purpose of drinking water for Chennai’s burgeoning population. The team noted that even though the lake has a water capacity of 3300 mc ft, the storage fluctuates sharply with the monsoons. Such a boom-bust cycle highlights the massive dependency on monsoons and weak catchment resilience.

The team noted that long term water security for Chennai is tied to this lake, and it needs a balanced mix of storage, conservation and alternate sources. They highlighted that sustainable management of the lake is key to prevent a Day Zero for a large city like Chennai.

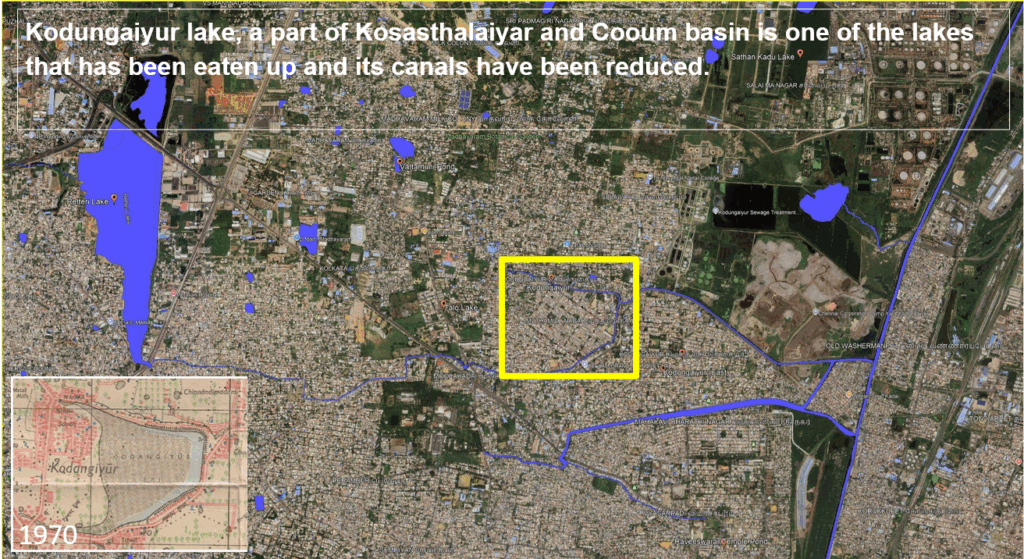

Kodungaiyur Canal System

Ajay, Divina, Faayiza, Jai, Nivedhini, Subhashini, Swarna and Vikashni analysed data on the lakes system that form the Kodungaiyur Canal – Ambattur, Korattur and Retteri lakes. They tried to look at the impact urbanisation has had on these lakes and how they have been affected.

They noted that Chennai’s rapid urbanization has destroyed its water bodies and disrupted the natural flow of water. The situation is no different around the Kodungaiyur canal system.

The team found that one of the lakes – Kodungaiyur Eri has in fact been completely lost and there is a government housing colony that has sprung up in its place, with the lake reduced to a canal. In the case of Retteri lake they found that a road had cut the river into two parts with very little flow between the two.

The team recommended that local stakeholders be involved in the decision making process, and a scientific approach involving experts is needed in mapping, restoration, reclamation and maintenance of lakes. A cell for water systems needs to be created under the environment cell to focus mainly on water systems, they suggested.

Adyar River System

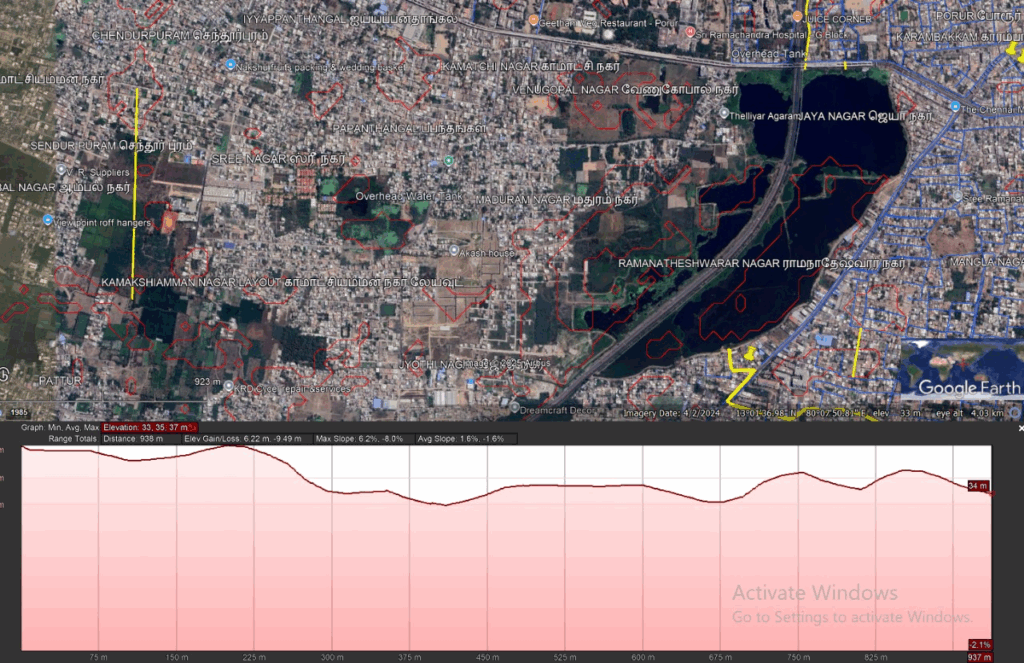

Karthik, Karthikeyan, Mira Srinidhi, Raghu, Raju and Yugapriya analyzed the state of the Adyar lake system with a focus on the Porur lake area and localised flooding in its surroundings.

The team noted that the area around the Porur lake can be divided into two halves, west and east with the Chennai-Maduravayol bypass bisecting the area. The west half of the area sees heavy inundation every year as compared to the eastern half.

They noted that the cause of this difference is the highway itself which obstructs the natural flow of floodwater from west to east. There are few points at which the water is allowed to cross the highway which is the cause of the waterlogging on one side of the road.

They recommended that the storm-water drain network needs to be connected properly. The MS Swaminathan Park could also be connected to the stormwater drains in this area which can help the park achieve maximum utilisation of rainwater.

Kovalam River System

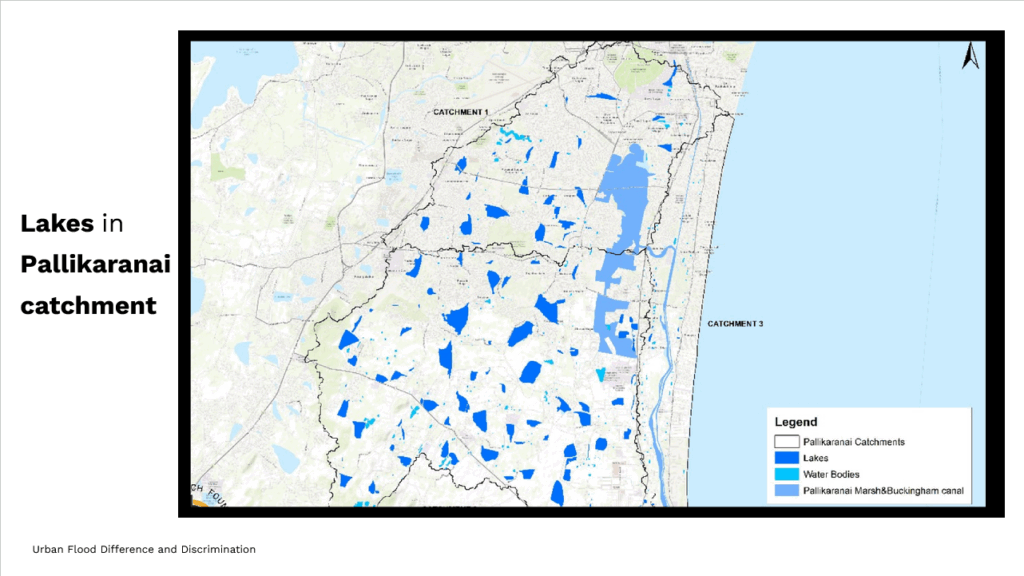

Benisha, Jeffrey, Lokesh, Ramya, Samsthithaa, Saravanan, Sethu Bhaskaran and Shivanesan looked at the southern lake system of Perumbakkam, Velachery and Perungudi from the perspective of flooding with a focus on its socio-economic dimensions.

The team mapped the vulnerable zone of the Pallikaranai catchment, and noted that the groups most affected are people living in resettlement colonies and marginalised women in the slum areas of Perumbakkam and Semmenchery. These colonies are situated next to the Nookampalyam canal and are subject to regular flooding due to the overflowing of the canal.

Despite successive governments spending hundreds of crores on improving the stormwater drain capacity of the area the problems persist. The team recommended that urban planning should be inclusive and prioritize vulnerable communities, that wetlands and natural drainage systems should be restored as a priority, and that strong climate adaptation strategies should be implemented.

Koovam River System

Ammu, Anandhakrishnan, Aravind, Gobica, Prashanth, Raguv, Rakshith and Subbishta analysed the Koovum river system from the perspective of its cultural and historical significance, and contrasted it with the current condition of the river and its lakes.

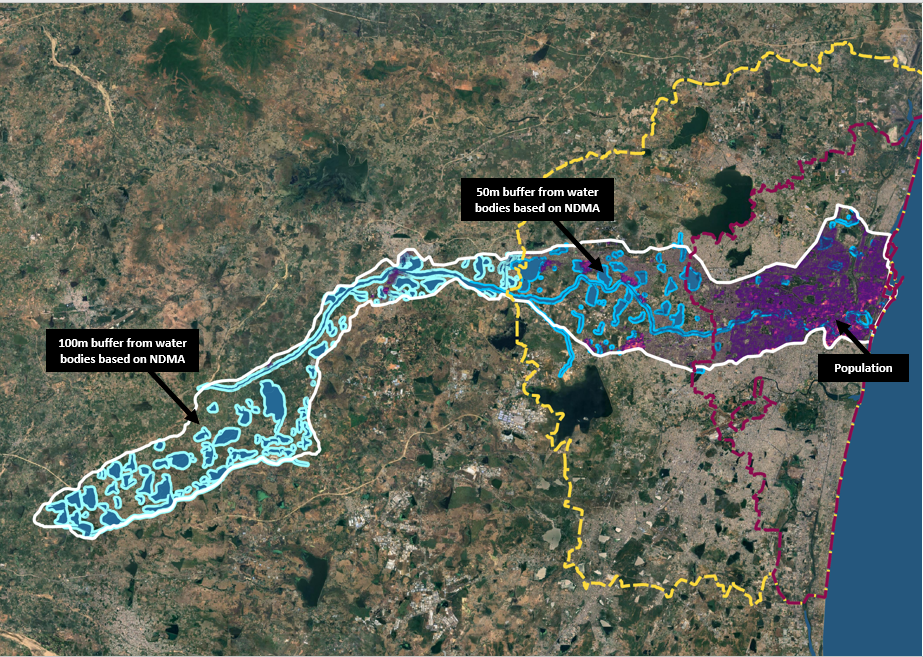

They noted that the river Koovam originates at the Kesavaram Anicut and is a distributary of the Pennar river. It then branches into two rivers, the Koovam and the Kosasthaliyar both of which flow into the Bay of Bengal after passing through Chennai. The river stretches over a distance of 115 km of which 25 km is inside the city.

The river starts in rural areas, passes through peri-urban areas as it approaches Chennai and then through the highly dense urban areas of the city. As per the census data, 31000 households live in the water shed area of the river inside Chennai, as against 11,00 in the peri-urban Chennai Metropolitan Authority extent outside GCC. In the rural parts, less than 10000 households dot the watershed. The urban and peri-urban households contribute 20.7 Million Litres of Sewage daily which flows through the river.

The team recommended that construction along waterbodies needs to be prohibited. To this end they highlighted the mechanism of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) to protect natural ecosystems. TDRs can involve the private sector in developing, conserving, restoring and maintaining the water bodies, with built-in safeguards to prevent misuse.

Conclusions

The teams highlighted how the different lake systems in Chennai serve different purposes and how some have been repurposed to serve purposes they were never intended for.

In the case of the Puzhal lake the lake serves the water supply needs of the city with no further lakes downstream of the Kosasthaliyar river, even historically. However, in the case of the Kodungaiyur canal, there have been lakes lost to urban development and the canals have been encroached upon causing regular waterlogging and inundation in the surrounding areas.

A similar situation was observed in the Porur lake catchment, where a highway has affected the natural flow of water and resulting in regular waterlogging on one side of the road. In the case of the southern system of lakes, the waterlogging was found to disproportionately affect those from the marginalised communities.

The Koovam river is a historic artifact which has been in habitation for many millennia. But the current status of the lake is of a sewage channel stretching through the city. The team highlighted the need to restore the river to its long lost glory.

Sahana Charan, Senior Editor, Oorvani Foundation noted that “Chennai is battered every year by rains and has become increasingly susceptible to flooding, and it is the lakes and wetlands that protect the city by acting as natural sponges. But, many lake ecosystems are under threat of indiscriminate construction by real-estate developers, garbage dumping and diminishing water quality. At the Chennai lakes datajam, it was interesting to see how the different teams looked at some pertinent issues such as flooding, changes in built up area around the water bodies and came up with recommendations and solutions for these problems.”

According to Sowmya Kannan, Researcher on Sustainable mobility and Road Safety at CAG “The datajam brought data into the heart of problem solving for Chennai’s lakes. By turning raw information into insights, it empowered citizens to craft smarter, community driven solutions and build stronger cases for protecting our city’s water bodies.”

Joel Sheton, Consultant at WELL Labs added that “events like datajam should be conducted very often to create proactive and responsible citizens to build on solutions for the existing problems around them and their neighbourhood. Exploring this space, I was able to network a good number of young minds who are ready to deep dive into the issue and discuss among their groups to derive a sustainable solution using tools like QGIS, Google Earth Engine, Google Earth / Google Earth Pro, etc.,”

Lokesh Parthiban, Poovulagin Nanbargal felt that “bringing people together from different walks of life to work on issues that affect them, like urban floods is important. Data jams like this expose people to understand these issues as they interact with different people and the data that we have in the open source.”

For Anjana Vencatesan, Senior Researcher, Care Earth, it was her organisation’s first time partnering for a datajam and “it was encouraging to see a great turnout and participants from varied backgrounds working together on brainstorming about Chennai’s water issues. It was particularly interesting to see how various teams honed in on various aspects rather than focusing on only one theme.”

For Karthik from Aram Thinai who participated in the event, “it was an interesting day working on a real-life problem with a new group of enthusiastic participants. Churning through maps, data and news articles we were able to understand problem statements and ball park responses to issues of flooding in Porur area. The group interactions were very interesting and inspiring.”